Post Views: 3,953

What's the deal with CANO

CANO Health Inc. (CANO) has been in the event-driven / special sits bucket for about a year ever since activists agitated for a sale of the company. The stock shot up to ~$10/sh in late 2022, only to nosedive back to $1.5/sh as of the February 2023.

Market’s pre-occupying concern with this name is whether it will get sold / whether the name is a good long at this level.

This series of posts offers my take on the whole situation.

Company Overview

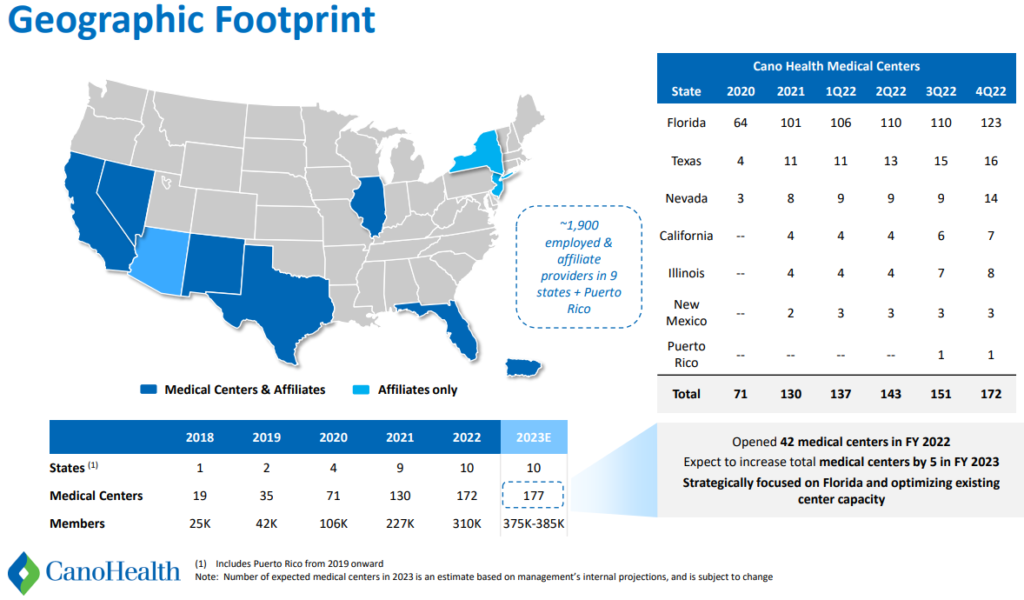

CANO Health Inc. (CANO) is a Primary Care Provider (PCP) for patients who are predominantly under Medicare Advantage (aka Medicare Part C) or Medicaid. As of Q3/22 (latest quarterly disclosure), CANO employed ~400 providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) across 151 owned medical centers and maintained affiliate relationships with over 1,500 physicians and ~900 clinical support employees. Most of the company owned medical centers are concentrated in Florida (110 out of 151). Per the most recent guidance, the company planned to grow to 170 company-owned clinics by YE2022.

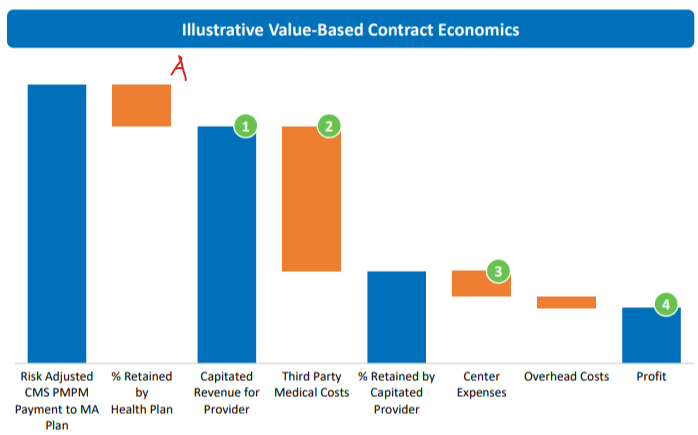

CANO makes money under what’s called a “capitated model” in which the healthcare payor pays the healthcare provider a fixed fee on a per month per patient basis, for each patient under the provider’s care. This fee then becomes the healthcare provider’s budget to treat each patient. Whatever unused/residual amount leftover from this fee becomes the profit to the healthcare provider. This model of healthcare has been instituted in recent years as the US aspires to transition from the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) model to a “value-based” healthcare approach. Under the FFS model, healthcare charges are incurred for each healthcare act/service performed, thereby presenting an inherent economic incentive for healthcare providers to elect to perform more healthcare services/diagnostics that may be profitable to the providers but excessive for the patient and inflationary to healthcare system. Though not without a different set of flaws, the newly incepted Value-Based model seeks to lower unnecessary costs by compensating healthcare providers – including physicians, hospitals – based on the healthcare outcome of the patients. Integral to this approach is that the healthcare payor controls healthcare costs by pre-determining the fixed amount per month per patient paid to the healthcare providers. The fee is calculated with considerations to 1) cost of care in the patient’s local market and the average utilization of services by the patients enrolled; 2) providers competitive bidding process with CMS; 3) the risk score of the patient – or how sick / what / conditions the patient has.

This value-based structure purportedly saves costs by capping the cost of healthcare (which is pre-determined by the fixed fee before care is rendered) and incentivizing healthcare providers to minimize actual healthcare costs, so as to stay within the budget of what’s paid to them and even generate a profit for themselves. Evidently, this Value-Based approach is catching on in the US as stats from healthcare providers and payors are often cited to illustrate this model has been successful in reducing cost of care while improving treatment outcomes for patients.

In CANO’s case, an array of healthcare insurers offering Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and ACA plans receive funding from the CMS fixed fees on a per month per patient basis; these insurers take a cut from this amount for their service in administering the plans (red A below), then pay CANO the remaining fixed fee (green #1 below), which becomes revenue for CANO. CANO in turn pays a portion of this amount to third party medical providers such as hospitals, surgery centers etc. (green #2 below). The leftover portion to CANO funds CANO’s costs of cares (green #3 below), and the residual amount becomes CANO’s profit (green #4 below).

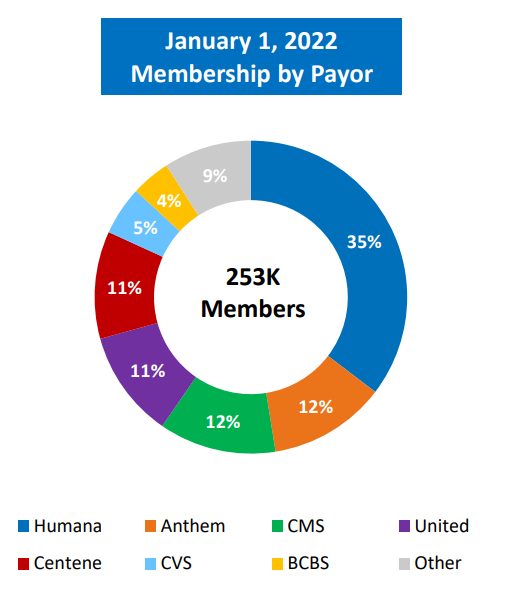

CANO has relationship with more than half a dozen Medicare Advantage and Medicare plan providers. CANO’s biggest payor is Humana (HUM), which I estimate as of YE2022 accounts for roughly 1/3 of CANO’s patient count.

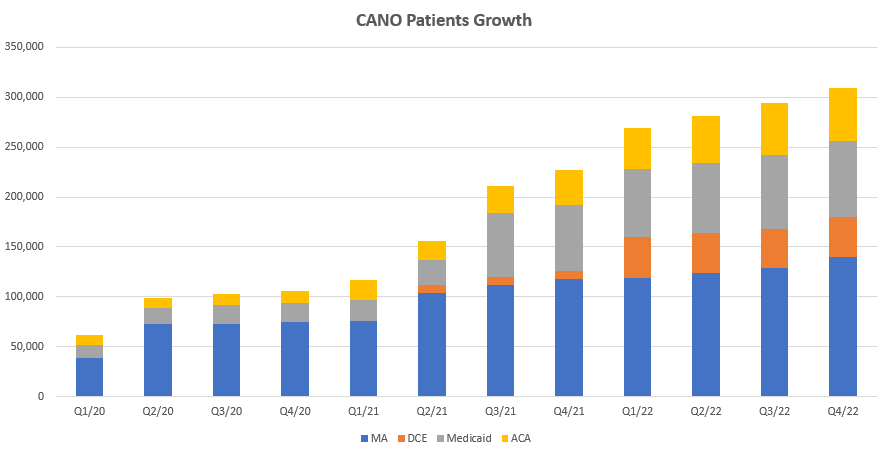

Over the past 3 years – for which 10 Q/Ks disclosures are available – CANO’s growth has been robust as the number of patients under CANO care grew from 61k at the end of Q1/20 to ~294k at the end of Q3/22.

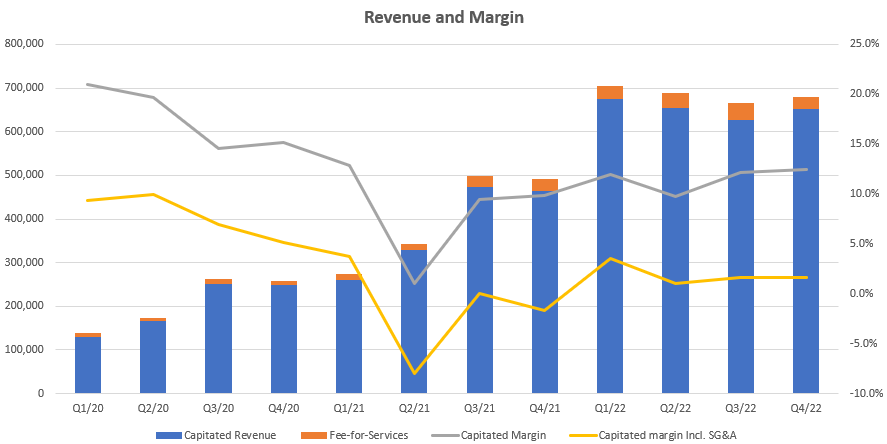

Revenue grew in tandem with patient count, but capitated margin (profit margin after deducting 3rd party medical expenses and direct cost of care incurred by CANO) tumbled in 2020 and has not recovered.

This is because 1) Covid-related hospitalizations and care incidents are purported by management to have been elevated cost of care in 2021; 2) there is a downward pressure on revenue per patient as new patients to CANO – for whom CMS pays a lower fixed-fees per month – diluted CANO’s revenue base. SG&A excluding stock comps have also risen, from 12.4% in 2020, to 13.9% in 2021, to my estimated 14% in 2022 based on Q1 to Q3 results and Q4 guidance.

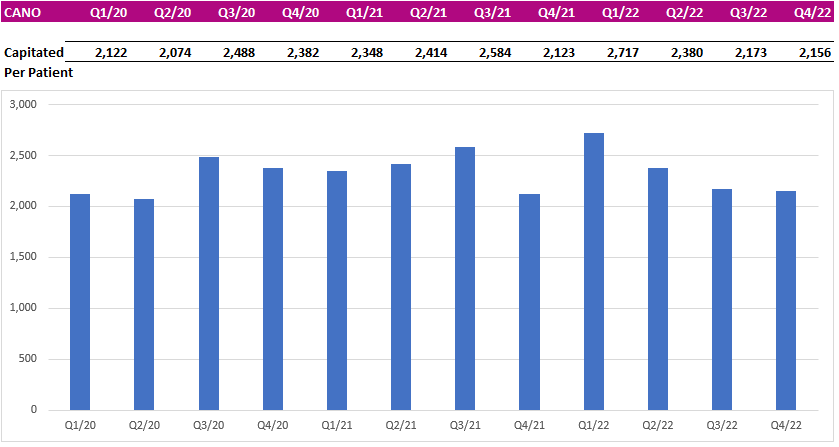

Some CANO figures diced differently reveals that revenue per patient essentially stood stagnant over the past 3 years, so all of the revenue growth came from CANO aggressively adding new patients via a combination of organic growth / building new medical centers (aka. de novo) and M&A / milking the affiliate physician programs, but the growth has been only achievable by incurring heavy cash outflow (more on this later).

The Story of CANO Thus Far

A – After opening in June 2021 at ~$15/sh implying a valuation of 2.6x EV/NTM Revenue, CANO tumbled to around $6/sh (implying a 1.1x EV/NTM Revenue) within a year as fervor around SPACs and healthcare stocks cooled.

B. While CANO lulled in the doldrum of $6/sh range, sentiment of a takeout started to percolate as One Medical (a non-capitated Primary Care Provider) was announced to be acquired by Amazon at 3x EV/REV and activists had honed in on CANO for a sale. On Aug 22, 2022, Owl Creek urged CANO for a sale. The stock moved higher on the news.

C – On Sep 22, 2022, CANO announced it’s weighing a sale, the stock jumped to $9/sh as the market contemplated a potential takeout of CANO by CVS, which had expressed willingness to conduct M&A to expand into Primary Care.

D – On Oct 17, 2022, news floated that CVS was not interested in CANO. The stock cratered from $9/sh to $4/sh.

E – On Nov 10, 2022, CANO cut guidance and lowered EBITDA estimate for 2022. Stock halved again from $4/sh to $2/sh.

F – Third Point, a major holder of CANO via the SPAC Jaws Acquisition Corp, exited remaining stake of CANO on Dec 8, 2022. The Stock took another dump, tumbling from $2/sh to close to a buck a share.

CANO now trades at $1.5/sh. Save a group of retail bagholders praying on Twitter, bullish sentiment appears to have vacated CANO. The stock doesn’t look like it’s about to climb out from the bottom of the well anytime soon.

What are the problems at CANO

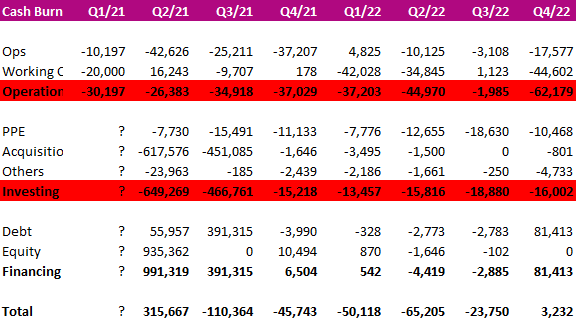

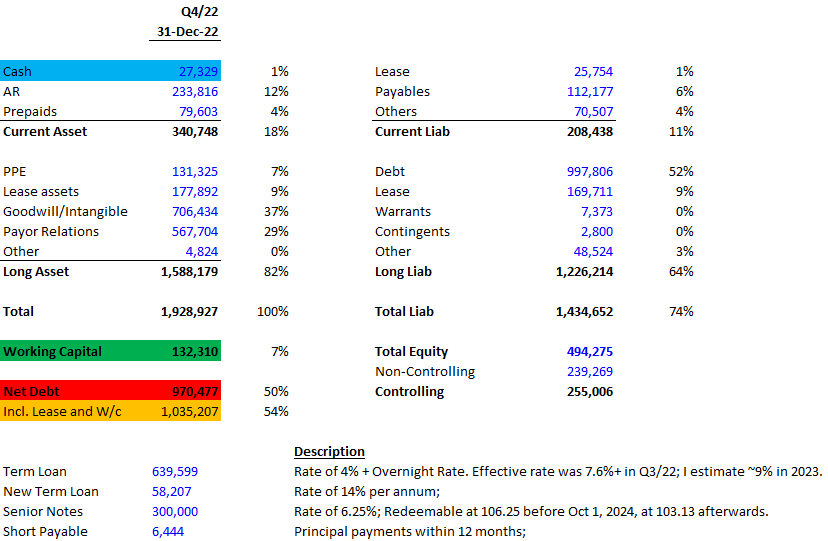

Problem #1 – the debt load. Still cash flow negative, CANO has been burning cash at a quarterly rate of ~$30mm from operations and ~$15-$20mm in capex over the past 2 years.

In February 2023, the company obtained additional debt financing in the form of $150mm term loan facility bearing 14% interest rate per annum for 2023 and 2024, and 13% thereafter. Along with existing debt, interest payment alone for 2023 will be $100mm, of which $90mm will be paid in cash, outweighing 2023 Adjusted EBITDA expected at $75mm to $85mm. Plus another cash outlay of $15mm for capex in 2023, CANO will become even more indebted this year. I estimate leverage to increase to over 8x Net Debt / EBITDA… This is unsavory to say the least.

#2 – 2023 guidance already paints an underwhelming year. Following a disappointing Q3/22 in which revenue saw 7% miss from consensus because capitated fees per new patient turned out much lower than anticipated, Q4’s results came unremarkable – with 2023 guidance pointing to worse than 2022 margin as the growing patient base evolves to include constituents characteristically fetching for lower capitated fees per head and higher medical cost.

As stated on Q4/22 call, patient growth in 2023 will be the slowest compared to the past 3 years because a very limited new medical centers will be build this year to conserve capex. The 65k to 75k new patients expected to join CANO in 2023 will also comprise of increasing portions of 1) non-risk MA patients (Medicare Advantage patients with lesser health issues – for which CMS pays a lower capitated revenue per patient) and 2) ACA patients (which fetch for much lower revenue per patient than even non-risk MA patients). The combining effect of this evolving patient base puts additional revenue pressure on CANO while correspondingly stresses the cost margin – which guidance already expects to be worse than 2022 (medical cost ratio of 81% to 82% this year vs. 79.1% for 2022).

Over the longer term, CANO maintains that capitated fees per patient would increase as new patients acclimate to CANO care and integrates onto the CANO platform… Based on my research, this essentially means that upon additional examinations of these patients, CANO will report more health conditions on the patients, bumping up the associated health risk scores of these patients, so that CMS will pay a higher capitated fee for them… If so, this would be otherwise known as “Risk Score Gaming”, which apparently is actually well-practised in the industry…

However, given CANO’s saw no notable increase in capitated fees per patient over the past 3 years and 2023 is bound to be worse, I’m left without convincing precedent that CANO can increase fees per patient over the longer term…. So following a disappointing 2022, 2023 looks pretty abysmal to me; and revenue and margin growth for the beyond hangs in the unknown.

#3 – The longer term concern for CANO in my view is whether there’d be a strategic buyer for it… This should be the most imperative consideration as the primary care business without a prospects of a strategic buyer simply does not stand on its own as an sufficiently lucrative business for non-financial buyers. Keep in mind that Primary Care for the likes of CANO is low margin business. These providers ultimately receive ~5% of the gross capitated fees paid by the CMS. Margin improvement is arguably limited as well since the main point of the capitation model is to save money, and a thickening margin for providers would indicate to the payor overpayment, prompting CMS / payor to lower fees in the future so as to rectify the overspend. Therefore, margin improvement is constrained by the conflicting regulatory interest to keep healthcare cost low.

Topline growth for PCP is also effectively capped as the source of revenue is Medicare/Medicaid spend. This budget is determined discretionarily by the government every year and grows at most high single digits per year. Conceptually, I’d further posit that capitated revenue per patient should grow at an annual pace of inflation + a perhaps a few percentages at most. A faster pace than this would have to be justified by a higher expected costs of treatment per patient, something that may happen if the patient becomes sicker over time, thereby requiring more healthcare services. But if CANO and capitated PCPs do a satisfactory job in their care of patients – as purported by results of improved patient health outcome – then average patient conditions should improve, requiring less healthcare treatment over time, so capitated revenue per patient should justifiably decline on inflation-adjusted terms… This dynamic constitutes an inherent impetus for CANO’s topline growth.

Given these structural limitations, the only group of buyers still incentivized to acquire PCPs is healthcare insurers looking to vertically integrate healthcare plans with the actual provision of healthcare services. Indeed, this has become an emergent trend enacted by large healthcare insurer/payors. Increasingly, healthcare plan providers are looking to consolidate healthcare service providers to whom actual care had to be outsourced and paid for. Over the past year, CVS had been the most vocal and explicit in announcing to the market willingness to acquire PCPs as a vertical integration play. In my view, there currently exists no other healthcare payors more ready to acquire a PCP at this time than CVS had been, but CVS made a pass on CANO and bought OSH instead…

CANO has just been left at the altar, waiting for another strategic buyer to turn up a move; but with no immediate buyers buoying CANO prospects, the stock has gone totally flaccid.

In the next piece, I’ll walk you through my list of pertinent healthcare plan providers that could still make a play for CANO.